Puzzle Monday: Does English Need a New Alphabet?

Editor’s Note, November 2024: Thanks for checking out our puzzle archive! While the online version of this puzzle is no longer interactive, we suggest downloading the PDF, available below. You can find other archived puzzle PDFs available for download here.

Among our crosswords and other puzzles, we feature linguistic challenges from around the world from puzzle aficionado and writer Alex Bellos. A PDF of the puzzle, as well as the solution, can be downloaded below.

Irish dramatist George Bernard Shaw—generally considered one of the greatest playwrights in the English language—was a controversial figure, who infused his many plays with his strident political and social views.

One of the causes he embraced most passionately was the very contentious matter of spelling reform. Yu red that rite! It barely needs saying that English spelling is a confusing mess in which letters, or combinations of letters, can be pronounced differently and sometimes not pronounced at all.

Shaw’s main concern was waste: time lost teaching children and foreigners a system full of irregularities, time lost in writing silent or redundant letters, and the paper and ink thrown away after them. The world would be a better place, he argued, if the alphabet had more letters so that every letter had a precise sound. “If the introduction of an English alphabet for the English language costs a civil war, or even […] a world war, I shall not grudge it,” he wrote. “The waste of war is negligible in comparison to the daily waste of trying to communicate with one another in English through an alphabet with sixteen letters missing. That must be remedied, come what may.”

Shaw was not the only prominent literary figure to campaign for spelling reform—in previous eras orthography warriors included the writers John Milton, Samuel Johnson, and Charles Dickens—but he was perhaps the most determined. When Shaw died in 1950 he left money in his will for the creation and promotion of an alphabet of at least 40 letters that will enable English “to be written without indicating single sounds by groups of letters or by diacritical marks.”

A competition for creating this was launched in 1957, and offered a prize of £500 (about $18,000 in today’s money) for the winning entry. By the next year, the judges had received 467 entries, and decided to split the money among the four best ones—none of which was determined to be good enough to be adopted as the new official alphabet of the English language. One of the winners, Ronald Kingsley Read, however, made adjustments to his submission, and the judges accepted this new version as official “Shavian,” the Bernard Shaw Alphabet.

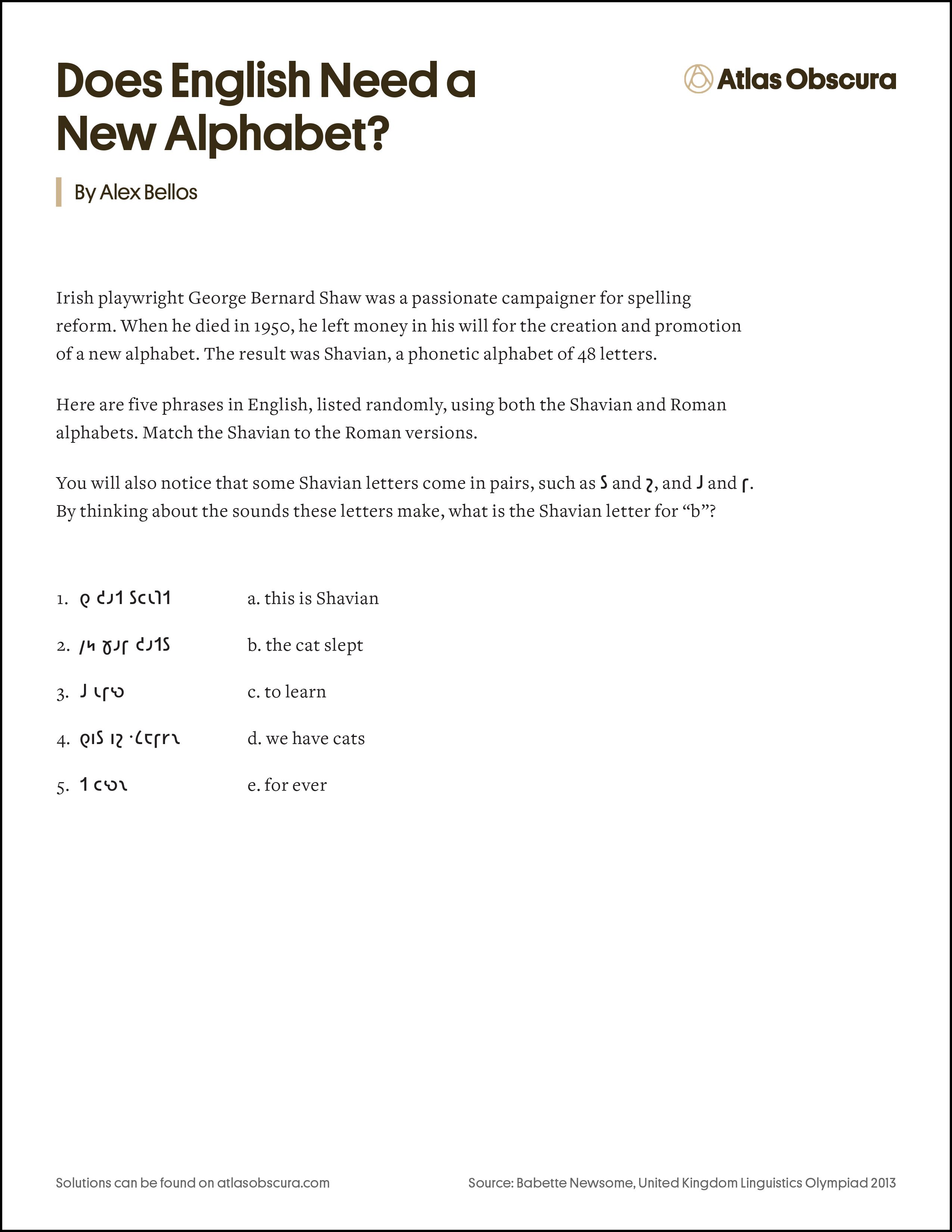

Shavian has 48 letters, and each is comprised of a single stroke so it can be written quickly and not take up too much space. The alphabet has other interesting features, one of which is revealed in the puzzle below.

The rest of the money designated for spelling reform in Shaw’s will was spent in 1962 to publish an edition of his play Androcles and the Lion, in which the text appeared in both Roman and Shavian alphabets. The alphabet, however, failed to catch on, and apart from a minimal online presence, the Shavian alphabet is now little more than a curiosity. Public interest in spelling reform has dwindled in recent years, though you never know where the next culture war will come from.

Richard Dietrich, founding president of the International Shaw Society and emeritus professor at the University of South Florida, says, “Most Shaw scholars seem to have lost interest in the Shavian phonetic alphabet, although it still stands as a monument to how innovative Shaw was or tried to be in making this a better world.”

Stumped? Download the solution, with all the logical steps to get there!

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook