Puzzle Monday: Official Language, Social Weapon

Editor’s Note, November 2024: Thanks for checking out our puzzle archive! While the online version of this puzzle is no longer interactive, we suggest downloading the PDF, available below. You can find other archived puzzle PDFs available for download here.

Among our crosswords and other puzzles, we’ll be featuring linguistic challenges from around the world from puzzle aficionado and writer Alex Bellos. A PDF of the puzzle, as well as the solution, can be downloaded below.

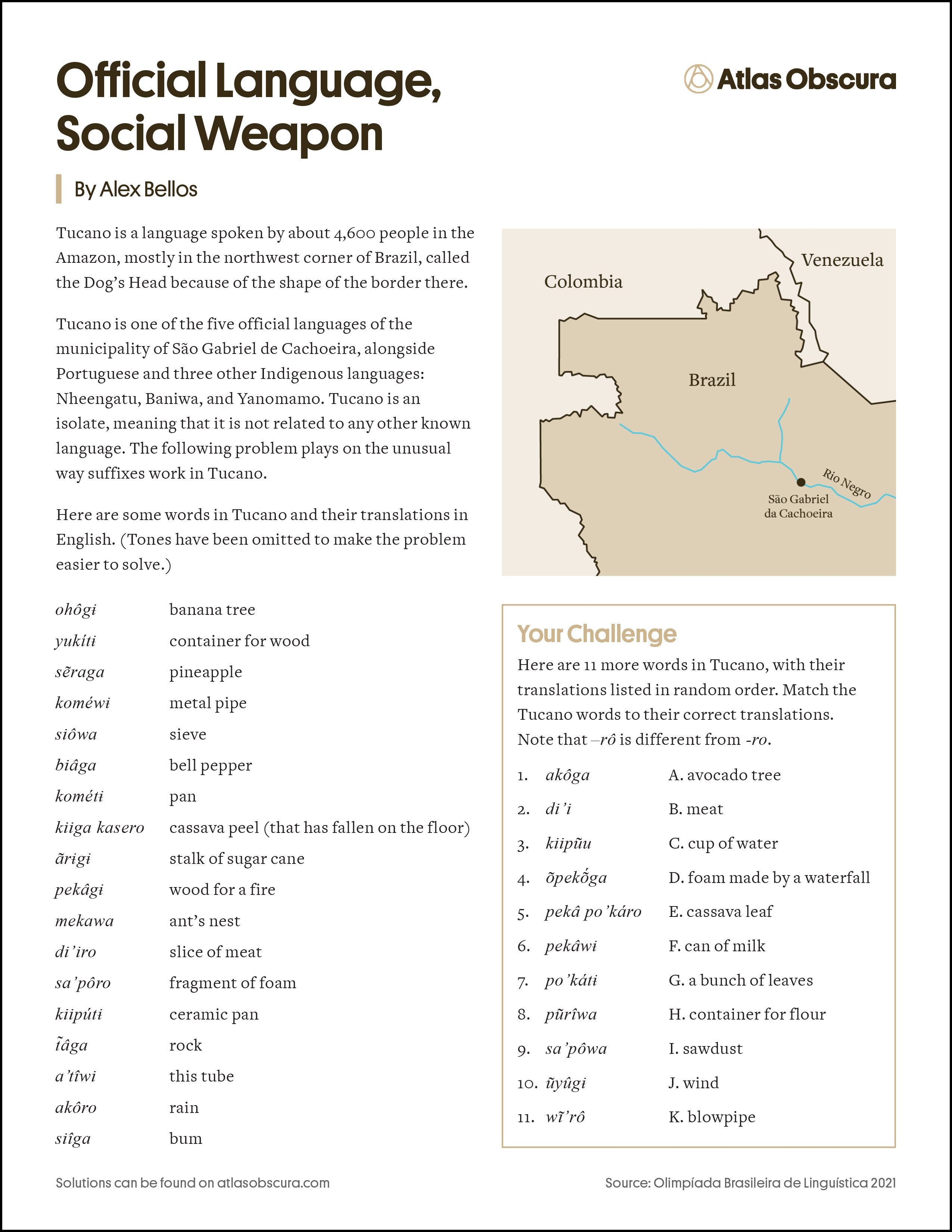

São Gabriel da Cachoeira, a remote municipality in the Amazon rain forest, is unique in Brazil: It has five official languages.

The municipality—an area the size of Tennessee, along the frontier with Colombia and Venezuela—has a population of about 46,000, about three quarters of whom are Indigenous peoples. The official languages are Portuguese, the national language of Brazil, as well as locally-spoken Tucano, Baniwa, Nheengatu, and Yanomamo.

The idea of legislating for official languages at a municipal level is a Brazilian innovation, designed to help preserve Indigenous languages, promote cultural pride, and improve social mobility. If a language has official legal status in a municipality, the hope goes, local state institutions will eventually offer all their services in that language, through take-up of this policy has been slowed by politics and a lack of funding.

“The whole project of ‘co-official languages’ is very recent,” says Federal University of Santa Catarina linguist Gilvan Müller de Oliveira, who is also the UNESCO Chair on Language Policies for Multilingualism. “But you need to see it as the start of a process that is very complex.”

Müller de Oliveira was one of the initiators of the legislation that gives local languages official status alongside Portuguese. São Gabriel da Cachoeira was the first place to apply the law in 2002, when it made Tucano, Baniwa, and Nheengatu “co-official.” (Yanomamo was added in 2017.)

Since 2002, nine other Indigenous languages have been made official in nine other municipalities across Brazil. These languages are, however, only a fraction of Brazil’s 200 or so Indigenous languages, which are spoken by around 350,000 people, or about one in three of the overall Indigenous population. All of these languages are considered endangered.

(In addition, nine European languages have been made official in municipalities in the south of Brazil, where there was much European immigration. These include languages no longer spoken in mainland Europe, such as Talian [a Venetian dialect], Pomeranian, and Hunsrik.)

Müller de Oliveira says that the introduction of co-official Indigenous languages must be understood as a small but important step in both saving these languages from extinction and improving the lives of Indigenous people.

“The 20th century was a century of persecution [for the speakers of Indigenous languages]. In the 21st century the tide is turning,” he says. “Now, communities see their languages as part of their culture. An official language is a social weapon.”

It is up to local government to offer services in all official languages, but this is barely happening. Local leaders often have other priorities, as well as a lack of funding. But it is also a reflection of the national political climate. Between 2019 and 2022, the Brazilian president was Jair Bolsonaro, a far-right ideologue who actively campaigned against the rights of Indigenous peoples. Now, however, the mood has changed. In January, the newly elected president (who also served from 2003 to 2010), Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, created a Ministry for Indigenous People, bringing hope to Indigenous communities that their interests, including the preservation of languages, will be better served by the federal government.

In addition to their social and cultural importance, the languages are also of great interest to the linguistics community.

Nheengatu (14,000 speakers) is a member of the Tupi language family, and was spread by Jesuit colonizers as a lingua franca for Indigenous people, and Baniwa (4,700 speakers) is from the Arauque language family. Two of the official languages, Tucano (4,600 speakers) and Yanomamo (20,000), on the other hand, are language isolates, meaning that there is not a family of other languages to which they belong. The puzzle below plays on one of the unusual aspects of the language.

Claudiane Menezes, a biologist who speaks Nheengatu and grew up in São Gabriel da Cachoeira, says that there has been an increase in the acceptance of Indigenous languages there in recent years. This is partly due to their status as official languages, and also a result of new education policy. “The languages are more ‘visible’ because schools are now obliged to teach a native language,” she says. “In a few public places—like the local notary—I’m told you can get attended by someone speaking in the official languages.”

Müller de Oliveira hopes that the co-official status of Indigenous languages will push local leaders in places such as São Gabriel da Cachoeira to introduce written materials in these languages. “The statistics are worrying. The census says that the number of native speakers of the Indigenous languages is decreasing,” he says. “If these languages are not being used in the internet, in digital form, young people will quickly start to use Portuguese instead.

“We really hope that things will change.”

Stumped? Download the solution, with all the logical steps to get there!

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook