We’re Sequencing Every Member of the Weirdest Bird Species on Earth

Meet the kākāpō—a nocturnal, flightless parrot who we are about to understand on an unprecedented level.

A kākāpō chows down on some berries. (Photo: Chris Birmingham/CC BY 2.0)

Getting endangered animals to reproduce can be a long, slow slog, full of turkey basters and hand puppets. But scientists have a new tool to aid procreation: Genetic sequencing, which helps researchers understand an animal’s vulnerabilities from the inside out, raising the likelihood of healthy offspring. Today, this high-cost tool is used sparingly—but if we could take it to the next level, mapping out the genome of every individual within a species, it could reveal a clear path towards that animal’s future.

So which endangered species are we going to do this for first? The noble tiger? The all-but-doomed black rhinoceros? The beloved, if pathetic, giant panda?

Nope. The winner is that freaky-looking green bird on the top of the page. If all goes according to plan, by some time next year, the kākāpō—a nocturnal, flightless parrot native to New Zealand—will be the first species in the world to have had every one of its representatives completely sequenced.

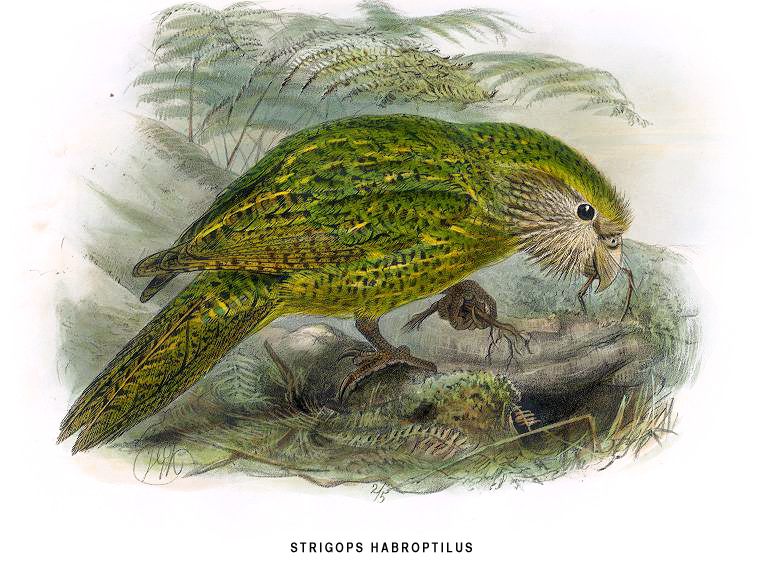

A kākāpō illustration from Birds of New Zealand. (Photo: Walter Lawry Buller/Public Domain)

New Zealand has only three native mammals (all bats), and the country is full of birds that have taken advantage of this lack of predators, acting more like rodents or weasels than your average winged creature. Kākāpōs are no exception. Their faces are covered in feathery whiskers, which they drag on the ground to help them navigate. They’re layered with body fat, and astoundingly heavy—the largest males can weigh as much as a housecat.

Their weight keeps them from flying, but they’re adept at climbing trees, scrabbling up the bark with extra-sharp claws and “parachuting” down with their wings outstretched, like hang gliders. Although technically parrots, they’re so far removed from even their closest relatives that they have an entire genus all to themselves. Even their official government information page calls them “eccentric.”

A kākāpō snuggles with a member of the Rescue Programme. (Photo: Department of Conservation New Zealand/CC BY 2.0)

These eccentricities worked well in a predator-free environment. But once humans brought rats and cats to New Zealand, they decimated the formerly thriving population. Ornithologists in New Zealand got serious about the kākāpō in the late 1980s, and set up a government-sponsored Kākāpō Recovery Programme. In the decades since, the Programme has relocated the entire kākāpō population to three small islands, which they’ve cleared of invasive predators. They have collared and named nearly every individual, and keep careful track of the bird’s family tree.

Their efforts have paid off, and the kākāpō population is up to 123, nearly triple its record low. But it’s still difficult to understand these weirdos. For one thing, they’re simply terrible at mating—they only attempt it every two or three years, when the fruit of their favorite tree, the podocarp, is ripe. When they do try, it’s often a bit pathetic. Males will climb the highest hill they can find, dig a hole, lie in it, and make a booming sound until an intrigued female wanders past.

One of the world’s least likely babies—a two-month-old kākāpō chick. (Photo: Dianne Mason/CC BY 2.0)

“In general, they perform pretty badly,” says David Iorns, founder of the Genetic Rescue Foundation, a nonprofit that has teamed up with the Kākāpō Recovery Programme to sequence the birds. “A lot of the time it doesn’t work. It’s really sad. They just sit up there all night long booming.”

Listed out, these peculiarities make the bird seem like a feathery, doomed poet, too good for this world. In person, the kākāpō is somewhat less romantic. Take the video below, from the BBC Two show “Last Chance to See.” “It ought to be impossible to describe a creature as looking old-fashioned,” host Stephen Fry begins, as a chubby male walks slowly over the forest floor. “But that’s exactly how [this kākāpō] looks, with his big sideburns and his Victorian gentleman’s face.”

Almost immediately, said Victorian gentleman climbs on top of Fry’s companion, zoologist Mark Carwardine, and begins vigorously humping the back of his head. He attempts to mate with Carwardine’s neck for a full minute, slapping his face with huge, green wings, grinning crazily, and letting out the occasional grunt-inflected screech.

Sometimes the freaky nephew gets the inheritance. Since February, Iorns and his colleagues have raised 85 percent of the $100,000 necessary to complete the project, and have steamed on ahead with the first set of sequences. For each one, scientists collect a fresh blood sample from the individual, chemically extract the DNA, and piece it together in the right order. Then, they annotate it, using completed genomes from other bird species to figure out which individual snippets match up with physical traits, like beak length or disease resistance.

Once every single individual is mapped in this way, they’ll be able to make the most of the couplings that do occur, preserving important differences between local populations, or matchmaking to ensure healthy chicks.

“Many of the problems that kākāpō face are genetic problems—inbreeding, infertility, disease,” says Iorns. “It’s only by having genetic information as detailed and complete as possible that we can begin to unlock many of the kākāpō’s secrets.”

Naturecultures is a weekly column that explores the changing relationships between humanity and wilder things. Have something you want covered (or uncovered)? Send tips to [email protected].

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook