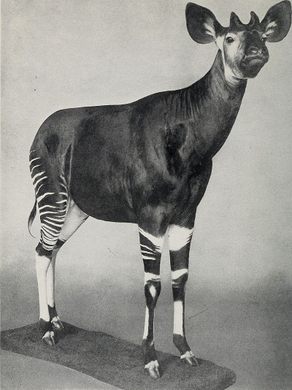

Okapi Taxidermy Diorama

This impressive scene portrays the elusive forest giraffe of Central Africa.

When you enter the Akeley Hall of African Mammals at the American Museum of Natural History, take a moment, if you will, to contemplate the fifth diorama on the righthand side of the gallery. In the dappled shade of a lush forested landscape stands an elegant pair of striped okapi, an unusual animal that looks like a cross between a zebra and giraffe.

In this diorama, one of the animals stretches its long neck to browse on the leaves of a bush, while the second is portrayed about to quench its thirst in a puddle of rainwater. Look carefully and you will spot a third okapi, which can be seen in the background where it stands behind the bole of a tree. This scene of the remote rainforests of Central Africa was meticulously assembled over 100 years ago to become what is widely considered one of the most impressive taxidermy dioramas in the world.

Today, the okapi, also commonly known as the forest giraffe, is a species that can be seen and admired in many zoos across North America, Europe, and East Asia. However, in the early 20th century, the sight of this unlikely ungulate, either living or dead, was completely impossible for anyone outside the Baka tribe of the Ituri forest. Due to the animals’ cryptic and elusive nature, which continually frustrated even the most intrepid explorers and naturalists, the enigmatic forest antelope remained hidden from the world and imbued with an aura akin to a latter-day unicorn.

By 1900, the only proof of the creatures’ existence were anecdotal references in the journals of explorers like Henry Morton Stanley and a few scant okapi skin artifacts obtained through bartering with Baka tribes. This prompted the president of the American Museum of Natural History at the time, Henry Osborn, to state that he wished to obtain an okapi specimen “before the progress of civilization should make this impossible.” In 1909, an expedition to the Central African rainforest was organized to collect specimens (living and dead) of this species, led by the German-born zoologist Herbert Lang and the museum’s ornithologist James Chapin.

After many months of travel, the pair eventually arrived in the jungles of what Lang would call “the most dismal spots on the face of the globe.” As they set out to find the animal, it became immediately clear that if the expedition was to have any success, it would depend entirely on the cooperation and help of the Baka (“pygmy”) hunter-gatherer tribes, who were the only peoples who knew the okapi and its habits well. Nevertheless, it took quite some time before the naturalists were able to gain the trust of Baka hunters to help them in their quest.

The task was made even more difficult by the humid conditions of the rainforest, which meant that the bodies of any animals caught in traps would decompose rapidly, attracting fungi and ants, which meant scientists needed to act quickly to preserve the skin. In spite of these difficulties, the expedition was eventually able to obtain the skins of three adult specimens as well as a live calf, which sadly died in captivity.

The okapi specimens were brought back to New York with much acclaim and attention from the international press, and the museum immediately began work on building a diorama to display them. The extraordinary attention to botanical detail in this particular diorama is remarkable. Every tree, plant, and fungus is a reproduction created with painstaking fidelity, portraying species that would naturally be found in the okapi’s dense and shadowy jungle habitat. This effect was largely achieved by the meticulous field data on the flora of the Ituri forest that was collected in the notebooks, specimen jars, flower presses, and photographs taken by Lang and Chapin during their expedition.

But despite appearances, not everything here is scientifically sound, as a practical joke was apparently played by the foreground artist George Frederick Mason on his fellow museum painter, James Perry Wilson. Knowing Wilson’s love of riddles and puzzles, Mason apparently painted a lilliputian intruder in the diorama—a North American striped chipmunk (which needless to say does not occur naturally in the Ituri forest nor any other African habitat)—and challenged him to find it. Eagle-eyed visitors may be able to spot this prank in the background painting if they pay close attention to the diorama’s forest floor.

Know Before You Go

The American Museum of Natural History in Manhattan is open from 10 a.m. to 5:45 p.m. every day. Entrance is free, but it is strongly recommended to contribute a small donation to the museum to help with its upkeep and outstanding scientific work. The okapi diorama can be found in the museum's Akeley Hall of African Mammals.

If you are interested in this species and would like to see a living okapi in the flesh, don't forget to check out the Okapi that are kept nearby in the Bronx Zoo as part of the "Congo gorilla forest" exhibit.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook